This blog post is part of our ongoing series exploring how business profits can be redirected toward life-changing charitable causes—without increasing costs for consumers. Here’s the journey so far:

- What is Profit for Good

- The Motivation Behind Expanding Profit for Good

- From Charity Choice to Competitive Advantage: The Power of Profit for Good

- Above-Market Philanthropy: Why Profit for Good Can Surpass Normal Returns

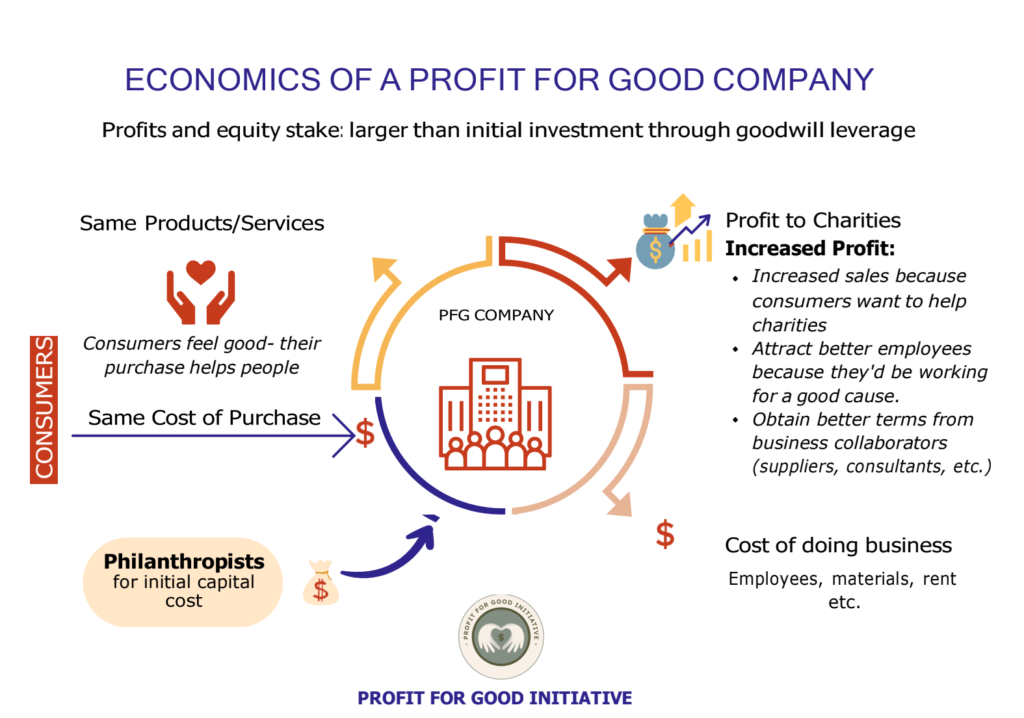

Imagine a world where your purchases can save lives or protect the environment. This is the promise of Profit for Good (PFG) businesses. My first couple blog posts attempted to resolve a few questions: defining what a PFG business is and clarifying why the successful expansion of PFGs would be a good thing for the world. This third blog post (excluding the post dedicated to announcing my TEDx Talk) is a more substantive one about why I think PFGs have an advantage over other businesses. My next blog post will explain why PFGs’ advantage over normal businesses allows them to be used as a tool to multiply their donations to charities.

The way I view the argument for PFG advantage is that it has two main premises. The first is that economic actors like consumers have a nonzero preference for some charities benefiting financially instead of random investors. This non-zero preference should translate into a tendency toward discriminatory action by these economic actors toward these charities, which I call Charity Choice, which would, in turn, translate into a business advantage. The second premise is that philanthropic actors are capable of using this Charity Choice phenomenon to create significant business advantages through PFGs due to the general absence of necessary costs to correspond with the Charity Choice benefit and the ability to choose business contexts where small advantages can be decisive. The post will briefly go over some of the strongest challenges to the PFG model and why I think they ultimately are surmountable, although some of these challenges and addressing them will probably be discussed individually in future blog posts.

I. The Existence of Charity Choice- A Non-Zero Preference by Economic Actors for Charities over Random Investors

One of the things that brings some people pause regarding the idea of Profit for Good is that it depends on everyday people. Most people do not donate to charities and if they do, donate to local causes rather than to projects in the developing world that can help people at rates orders of magnitude higher or fund animal shelter rescues where money could do tens of thousands of times more good for farmed animals. Most people in the developed world could lift multiple people out of extreme poverty, save someone’s life from malaria, and/or ameliorate torturous conditions for hundreds of thousands of animals in the factory farming system while still living comfortable and enjoyable lives. In any event, the degree of sacrifice that could profoundly better and/or save many lives is minuscule in relation to the good that could be achieved. In short, I recognize that people often prioritize their own needs and may not always make the most effective choices to help others.

But the critical difference between acting as a buyer (or other economic actor engaged otherwise with a PFG) and a donor is that donors are engaged in a personal sacrifice whereas this need not be the case regarding buyers from PFGs. In asking this question, we suspend the question of whether or not in fact PFGs are likely to be able to be as competitive (or more competitive) than non-PFG businesses along the relevant dimensions for consumers/laborers/business collaborators, which I discuss in section II. This section poses a simple question. A consumer has a choice between two products of identical quality, convenience, price, and all other relevant factors. One choice saves kids from malaria and the other enriches random shareholders. Would the average consumer, knowing all of the preceding, choose to buy from the PFG?

Research into consumer behavior towards socially responsible businesses sheds light on this question. According to Mohr, Webb, and Harris (2001), while consumers generally exhibit a favorable attitude towards companies that engage in socially responsible practices, this positivity doesn’t always translate into actual purchasing behavior. The study highlights a critical barrier: the assumption among consumers that opting for products from socially responsible companies may involve sacrifices in terms of price, quality, or convenience. This perceived, or actual, trade-off, detailed on page 68 of their study, often deters consumers from committing to purchases from such businesses.

However, the “Charity Choice” (“CC”) model posits that when consumers are assured there is no trade-off—when products benefiting charities are equivalent in price, quality, and convenience to their non-charitable counterparts—this latent positive attitude is more likely to convert into actual consumer choice. This is further supported by Basil and Weber (2006), who identify that both intrinsic values and concern for appearances motivate consumers to respond positively to cause-related marketing. They argue that when consumers see that their purchase could simultaneously help a cause and maintain social esteem without compromising product value, their pro-social preferences are activated, leading to a decision in favor of products that benefit charities.

The negation of the “Non-Zero Preference” premise presents a stance that is fundamentally hard to reconcile with basic human social instincts and ethical reasoning. To suggest that individuals would be wholly indifferent between purchasing a product that contributes to saving a child from malaria and one that merely enriches a random investor challenges the core of what many understand about moral behavior and social responsibility. This negation posits that consumers, when presented with two identical options except for the beneficiary of their expenditure, would have no preference whatsoever—even if one option directly supports a life-saving cause. Remember that this premise assumes equality of product choices in all other aspects and the consumers’ knowledge of this equality.

I contend that the rejection of this premise is not plausible. While the strength of this preference and the specific conditions that might enhance or diminish it certainly warrant further exploration and debate, the basic existence of this preference is aligned with both intuitive human empathy and empirical evidence. I bring this up because this basic notion, that people would rather at least some charities benefit than random investors, is difficult to dispute and pervasive, potentially affecting consumers, employees, and other economic actors. Essentially, it defies credulity to say that people do not care at all about money going to save lives or better the world as some effective charities do.

It’s important to acknowledge, however, that the real challenge lies not in establishing that this preference exists but in determining how effectively PFGs can translate this preference into a choice for consumers and other actors without complications. In the next section, we will argue for and establish the premise that Charity Choice can be translated into significant business advantages. This is bolstered by the distinctive benefit of PFGs not impairing operational effectiveness or efficiency—unlike many other ethical business practices—and by the universality of potential application of PFGs, which allows us to select and maximize the most advantageous contexts.

II. From Preference to Practice: Activating Charity Choice in Competitive Markets

Because economic actors like consumers may exhibit only a slight preference for charities receiving funds over random investors—what I refer to as “Charity Choice” (CC)—one might question the significance of this preference in the broader landscape of business success. If this inclination were dominant, we might expect a more substantial portion of the public to engage in charitable donations. Yet, despite its potentially modest scale, this preference can still be a pivotal factor. The challenge lies in whether we can leverage this subtle preference to create a significant competitive advantage for Profit for Good (PFG) businesses, enabling consumers and other economic actors to act on this preference without being overshadowed by other influential factors.

The second premise of the Competitive Advantage thesis is inherently more complex than the first. While it’s almost self-evident that, all else being equal, saving a child from malaria is preferable to enriching a random investor, the real question is about the practicality of building businesses that allow this modest preference—Charity Choice—to translate into a tangible, significant advantage. How feasible is it to offer consumers and other economic actors the opportunity to act on their slight preference without interference from other competing factors?

- No Additional Costs: Unlike many other prosocial business features, ownership by a charity or charitable foundation does not inherently entail additional costs.

- Universal Applicability: The PFG model can be applied to virtually any type of business, meaning there are diverse contexts in which PFGs might thrive, some particularly favorable.

- Scalability: If PFGs consistently outperform their non-PFG counterparts, the scale of potential leverage for philanthropy is vast. This opens up a spectrum of opportunities to explore how even a small Charity Choice can be amplified into a decisive factor in competitive markets.

A. Leveraging Charitable Ownership: Social Good without Business Compromise

One common misconception I encounter about Profit for Good (PFG) businesses is the concern that it might be inefficient for a charity to run a business outside its core mission. For example, skeptics argue that while the Against Malaria Foundation excels at saving children from malaria, it wouldn’t necessarily be effective at running a laundry detergent company like Tide. This concern overlooks a critical distinction: while a charity owns the business, it does not manage it. Ownership is separate from day-to-day management. Across various business sizes, insiders and affiliates only own a small fraction of equity—19.7% in small firms, 9% in mid-cap firms, and 4.9% in large firms. This means the majority of ownership stakes are held by individuals not involved in the day-to-day operations. Successful companies often insulate their boards and management from shareholder pressures using mechanisms like poison pills.

Moreover, the idea that frequent stock trading provides essential performance signals to management is challenged by studies on foundation-owned firms, where equity seldom changes hands. The generally passive role of shareholders suggests that PFGs, which prioritize charitable outcomes, do not inherently face operational disadvantages compared to traditional businesses. This ensures that the Charity Choice (CC) advantage doesn’t come with a corresponding business drawback.

However, there are contexts where equity ownership may matter. For instance, in some startups, the potential for significant equity gains can be essential for motivating key personnel. A PFG startup, by its nature, offers limited equity to non-charitable stakeholders. But as PFG gains recognition as a viable business model, philanthropists could step in to provide the necessary startup funding on behalf of charities. This approach might leave a slight disadvantage compared to traditional startups that reserve a larger equity share for founders and early employees. Yet, examples like Humanitix, a startup where all profits benefit charities, demonstrate the potential for meteoric success even within these constraints.

There are also scenarios where ownership by a charitable foundation would not impact the business operations—other than the positive effects of CC on sales, talent acquisition, etc. For instance, if a mid-sized to large business already has an effective governance and management structure, a charitable foundation could acquire the majority of shares without altering these operational aspects. The transition of Patagonia to a business where profits benefit charities exemplifies how private ownership can successfully convert to a PFG model.

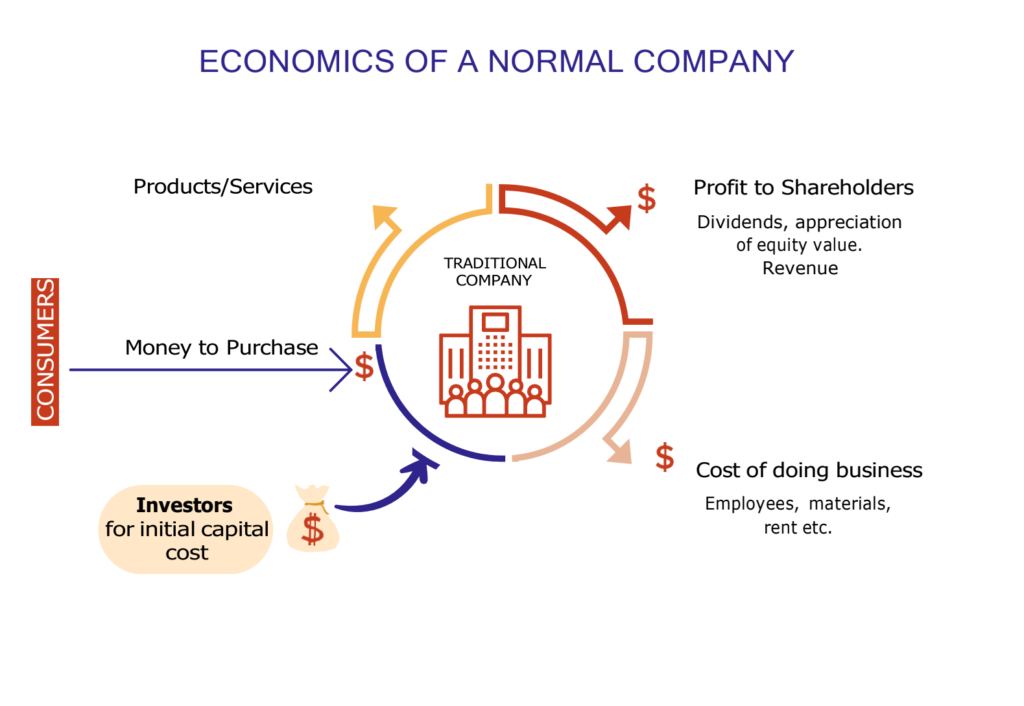

This distinguishes PFG from other prosocial business features that incur additional costs. For example, businesses committed to Fair Trade coffee face higher supply chain costs, which might be passed on to consumers. Or an environmentally friendly laundry detergent might underperform compared to a less sustainable competitor. Since the prosocial aspect of PFG pertains to ownership rather than operational features, there’s no structural reason for increased costs or diminished performance. Below, I provide a diagram illustrating the similarity between a PFG and a typical business.

The absence of added costs or performance impairments is a key reason for my optimism about the potential of PFG businesses. However, it’s not always obvious to consumers that there are no hidden costs in products from PFG businesses, leading to potential skepticism about any “catch” in products that market virtue. I will address this issue briefly in the final section on obstacles to PFGs.

B. Universality of the Profit for Good Model

A key strength of the Profit for Good (PFG) model is its universal applicability across industries. Whether it’s fast food, toothpaste, high-end clothing, or commission-based services like sales, PFGs can be integrated into virtually any product or service sector. Imagine if a business discovered a method to produce a specific component for clocks more cheaply than its competitors. This advantage would be confined to the clock industry. In contrast, the Charity Choice (CC) advantage of PFGs is applicable universally, cutting across all sectors.

The universality of PFG means that the potential business advantages created by CC can vary greatly depending on the context. Consider the restaurant industry, where factors like food quality, menu variety, location, ambiance, and service all significantly impact success. Moreover, a restaurant’s profitability is inherently limited by its physical size and geographic reach. In such a context, CC might not confer a substantial advantage because it may be crowded out by these wide varieties of factors.

However, in industries where businesses offer similar choices and prices to their competitors, the PFG model can provide a decisive edge. For example, BOAS sells vintage, high-quality jeans—a product familiar to consumers—that could scale globally. By offering similar products as its competitors but with the added benefit of supporting charitable causes, BOAS gains a competitive advantage that others cannot replicate unless they too become PFGs: consumers can save lives without paying extra. Similarly, Humanitix allows venues to sell tickets under terms comparable to its competitors but supports education in the developing world and other life-saving charities. Our organization is launching a project enabling individuals to buy identical life insurance policies at the same prices, but with commissions directed to fight childhood malaria instead of going to a random insurance agent (pitch deck linked here).

The question is not whether being a PFG always offers a significant business advantage, but whether there are contexts in which it does—and there are many such contexts where PFG could provide a decisive business advantage.

The scale of the potential good achievable through PFG is another significant aspect of its universality. Even if PFGs effectively leverage just 10% of the global economy, the impact could be immense. With annual profits in the global economy reaching $10 trillion, directing even 10% of that to effective charities tackling global poverty, environmental issues, or factory farming could make substantial inroads toward solving these problems. As the advantages of PFG become more broadly recognized, they can be expanded further using debt financing and leveraged buyouts on potentially favorable terms. I will delve deeper into how the competitive advantage of PFGs translates into a powerful financial tool for philanthropists in my next blog post.

The Profit for Good (PFG) model holds vast potential to turn the modest Charity Choice advantage into a significant competitive edge across diverse business sectors. By demonstrating that ownership by a charity or charitable foundation need not entail higher costs or diminished performance, and by illustrating the universality of the PFG model across various industries, we’ve seen how even a slight consumer preference can be leveraged for substantial business advantages. However, the path to realizing this potential is not without challenges. In the forthcoming section, we’ll delve into the hurdles that PFGs face.

III. Overcoming Obstacles: Ensuring the Success of Profit for Good Businesses

While the potential for Profit for Good (PFG) businesses is immense, a blog post on the competitive advantage of PFGs would be incomplete without addressing some of the most persuasive criticisms and obstacles that might hinder their success. For further discussion and engagement, I invite you to explore our criticism and redteaming document where you can raise your own concerns or address those of others.

Difficulty of Scaling Profit for Good without Traditional Investors

One significant challenge is the perceived difficulty of scaling PFGs without traditional investors who seek personal gain. Critics argue that PFGs might struggle to compete with incumbents that have massive economies of scale or that they won’t be able to attract the necessary capital for growth due to the non-traditional nature of their investment structure. However, if it becomes evident that PFGs offer a multiplier opportunity, philanthropists will be motivated to adequately capitalize these businesses. Early success in the most promising areas can serve as a domino effect—providing a solid evidence base that inspires further PFG investment and encouraging more philanthropists and financial institutions to support PFG expansion. As the evidence base expands, banks and other lenders could finance PFG growth through debt instruments as is done in leveraged buy-outs, significantly extending the reach of funding beyond philanthropic dollars. This challenge boils down to the discovery cost, which should be attainable. Educating charitable investors about the unique advantages of PFGs, particularly in areas with minimal differentiation or where Charity Choice can be highly influential, can make these ventures compelling investments.

Double Standards, Consumer Skepticism, and Strategic Sector Selection

PFGs may be perceived as needing to adhere to a higher ethical standard than traditional businesses, potentially facing higher reputational costs for engaging in competitive practices perceived as contrary to charitable missions. However, this perception can be transformed into an asset by clearly communicating how PFGs uphold ethical decisions without compromising commercial viability. For instance, companies like Patagonia and Ben & Jerry’s have successfully navigated this balance, maintaining strong ethical stances while thriving in competitive markets. Additionally, educating consumers about the overall benefits of PFGs can help shift perceptions. If consumers understand that PFGs, even when engaging in competitive business practices, still outperform traditional businesses in terms of social impact, they may prefer PFGs despite these practices.

Strategic sector selection is a critical part of addressing these challenges. PFGs have the flexibility to choose sectors where ethical and business alignment is clear, avoiding industries where competing requires behaviors perceived as unethical. Focusing on industries where the impact of Charity Choice is significant, PFGs can thrive by demonstrating that doing good and doing well are synonymous.

Perceived Trade-offs in PFG Products and Services

A major concern is the assumption that PFG products or services come with hidden costs or trade-offs, leading to skepticism about the no-sacrifice promise. Examples like Fair Trade coffee, which often comes at a higher price, or eco-friendly detergents, which may underperform compared to traditional options, fuel this perception. However, Charity Choice among other economic actors can also play a role. For instance, if a PFG can attract better talent due to its charitable mission, it may offer superior products or better prices. Similarly, business partners might prefer to work with PFGs, enhancing the overall competitiveness of their offerings. To counter consumer skepticism, strategic educational marketing is crucial. By initially expanding in sectors where products can be offered identically to competitors but with the added benefit of supporting charities, PFGs can build public trust. Demonstrating through well-marketed initiatives like the Commissions for a Cause project—where consumers receive the same service at the same cost but with commissions directed to charity—vividly illustrates the no-compromise nature of PFG offerings.

Motivation of Founders and Investors

Concerns that the best founders and investors may prefer wealth creation over funding charities overlook the broader landscape of PFG potential. While personal wealth is a strong motivator, PFGs can attract founders and investors by offering competitive market positions and the opportunity to disrupt existing equilibriums with a costless advantage—their charitable identity. The success of Humanitix, a startup where all profits benefit charities, demonstrates that PFGs can thrive even in the startup ecosystem. Additionally, the potential advantages of PFGs can outweigh the need to offer a bit more initial equity to founders and early employees. Moreover, in the majority of businesses, the vast majority of shareholders are not involved in the business operations, similar to how charitable foundations would operate as equity holders. PFGs would be governed by a separate board of directors, consisting of governance professionals akin to those in traditional for-profits. This model is still about maximizing profits; the difference lies in who benefits. Charitable foundations as shareholders still desire strong company performance to access large funds for their causes. The PFG framework aligns with free-market principles but adds a layer of consumer goodwill that offers a competitive edge.

Conclusion

The case for Profit for Good (PFG) businesses rests on two foundational premises. First, the concept of Charity Choice (CC) reflects a non-zero preference among economic actors for supporting charities over enriching random investors. This preference, even if modest, is a real and pervasive factor that can influence consumer behavior when the choice is clear and the perceived costs are neutral. Empirical research and intuitive human empathy support the existence of this preference, making it difficult to deny that people would generally prefer to see their money benefit effective charities rather than anonymous shareholders.

Second, PFGs have the potential to leverage this Charity Choice into significant business advantages. Unlike many other ethical business practices that might incur additional costs or compromise performance, PFGs can integrate charitable ownership without these drawbacks. This unique aspect, coupled with the universal applicability of the PFG model, allows us to strategically choose contexts where even a slight preference for charitable outcomes can lead to substantial competitive benefits. From consumer products to commission-based services, there are numerous sectors where PFGs can outshine their traditional counterparts by offering the same value proposition with the added benefit of supporting worthy causes.

Addressing some of the biggest challenges, such as scaling without traditional investors and overcoming consumer skepticism, involves strategic sector selection and robust educational marketing. By focusing on areas with minimal differentiation and demonstrating the tangible benefits of PFGs, we can build a strong case for these businesses. The early successes in the most promising sectors can create a domino effect, inspiring further investments and expanding the reach of PFGs.

In the next blog post, we will explore how the competitive advantage of PFGs can be harnessed as a powerful multiplier opportunity for philanthropists. By directing profits to effective charities, PFGs can amplify philanthropic impact, providing a scalable and sustainable way to address some of the world’s most pressing issues. Just about anyone would prefer to see their money make a positive difference in the world rather than simply increase the wealth of random investors. We have the capability to offer people this choice, turning a modest preference into a transformative force for good.

Stay tuned as we delve into how leveraging the Profit for Good model can enable us to save lives, reduce suffering, and ultimately, save the world.

GET UPDATES ON GOOD THINGS THAT MATTER IN YOUR INBOX.